The first week of December will probably be remembered as “that time the ECB thought rates weren’t negative enough and decided to drop them by another 15 bps “. However, the central bank did more than just lower the rates:

- QE was extended until such time as the ECB sees fit

- A lot of confusion seems to have been generated about the ANSA.

- some details were provided about Greek coverage by QE, and

- Geopolitical risks were acknowledged.

The decisions were not unanimous but there was an overwhelming majority in support. This post reviews what I (arbitrarily) consider the most important points.

The Deposit Rate Cut

First of all, the ECB lowered only one of the rates, out of a total of three rates it controls in its standard operations. The rate being lowered was the deposit facility rate, ie the return that the ECB offers on overnight deposits. An alternative way to think about it is that the ECB just increased the cost that banks pay for sitting on their cash rather than lending it to each other or the real economy.

Meanwhile, the cost of borrowing from the ECB has remained stable at 0.3% for a 1 week repo with (the ECB) (MRO) and 0.5% for an overnight loan (Marginal lending facility). Any lower than this and the ECB will start paying banks to take its cash.

Extending & reinvesting principal payments from APP and Buying sub-national debt under the PSPP

The ECB took three additional decisions regarding the coverage of its QE programme:

- To extend the Asset Purchasing Programme (APP = ABSPP + CBPP3 + PSPP) by at least 5 months from the original deadline of September 2016 to March 2017.

- To reinvest principal payments from the APP indefinitely, thus extending QE indefinitely.

- Finally, the ECB has also decided to extend its public sector purchasing programme to cover subnational government markets, including municipal and state/region/provincial debt.

ECB Logic: If a little is good, more is better

On the surface, these decisions were motivated by the fact that euro-zone inflation is 0.1% in November, so 190bps short of the 2% target and 90bps away from the 1% forecasted for the end of 2016. At the same time, money growth is being driven by base money, which suggests that banks are not lending enough money.

However, Draghi argued that an ECB negative rate with QE is working, and that the reason that the deposit facility rates were further lowered is because the policy is not working fast enough.

The logic that the policy is working is motivated by encouraging quarterly growth figures for consumption

“The growth rates in this year have been 0.5%, 0.4% and 0.3% over the last three quarters.”

… and increases in inflation…

” our policies have been effective also on the inflation front, because (…) the correlation between our inflation expectations measures and the current inflation or the oil prices has decreased or has just disappeared. “

Causes of Financial Success

The success of QE has been obvious in financial markets. According to Draghi, QE exceeded the ECB’s expectations because it was planned prior to the deterioration of conditions in emerging markets and the collapse in the price of oil, both of which supposedly drove investors to fixed income markets, I presume.

Causes of real Failure

I suppose the most common explanation for the lack of real economic growth is lag. Logic argues that the transmission of monetary policy from financial markets to the real economy, orthodox or otherwise, takes time, particularly after a crisis. Banks need to fail and those that survive need to fix their balance sheets.

Given the nature of the EZ crisis, stress testing is too political to be accurate. When this exercise has been conducted in te EZ a lot the scenarios tended not to stress the sovereign too much because more severe ones may have undermined the market’s perception of ECB confidence of EZ sovereigns. As a result, it’s very likely we still have a lot of zombie banks dragging their financial carcass around and slowing down the rest of the herd.

Ultimately, as long as the balance sheet of MFIs is stagnant, I doubt that there will be proper growth.

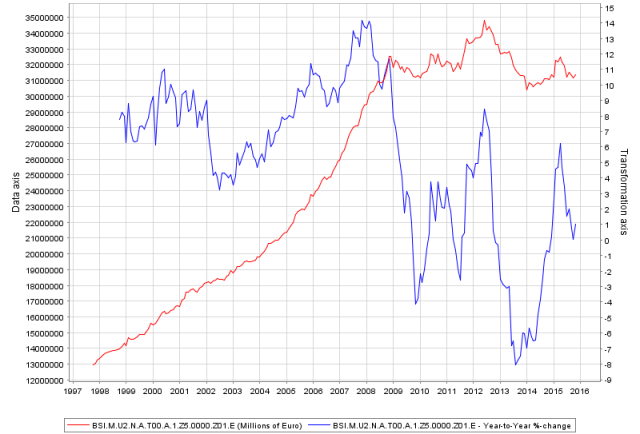

(Variable: “total assets/liabilities”; Red curve total stocks; blue line is Year-on-Year change %)

Particularly when the balance sheet total is so correlated with loans to non-financial MFIs (corporates).

(Variable: “Loans, Total, Outstanding amounts at the end of the period (stocks), Euro area (changing composition), Non-MFIs excluding general government, Euro”; Red curve total stocks; blue line is Year-on-Year change %)

Interestingly however, the ECB’s take (on this occasion), was that

“There are many factors that affected the core inflation projections as we had it since January 2015. The most important ones I’ve just mentioned: it’s the oil prices, and the situation in the emerging market economies. What we’ve done since then is to create very favourable financial and credit market conditions so that firms and households, even though burdened by these external factors, could find credit easier to access and more abundant.”(emphasis added)

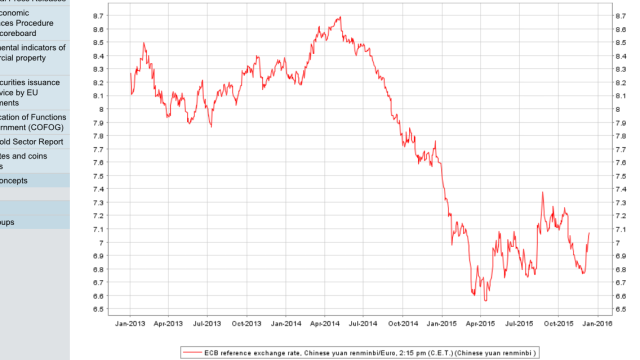

This is interesting because I don’t really see firms and households as being “burdened” by these factors, certainly not in a way that significantly impacts inflation negatively. To my knowledge, and I could clearly be missing something here, there’s one channel through which nflation could be held back by the appreciation of the Euro via-à-vis emerging market currencies: purchasing-power parity (PPP). However, that would require some pretty extreme facts.

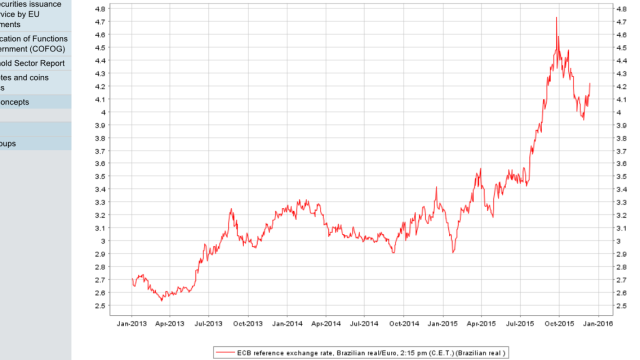

Remembering that PPP suggests that a currency appreciation leads to a less that proportional decrease in inflation, or more popularly that a depreciation causes an increase in inflation, and that this exchange rate pass-through occurs through imports, my understanding is that the inflation decreasing effects of the Euro vis-à-vis the Brazilian real (BRL)…

… and the SouthAfrican Rand (ZAR).

Had a more powerful lowered the cost of our collective consumption so much that it was not only noticeable but also, it was able to completely overwhelm the the fact that the Euro depreciated against the US dollar (USD)…

Now that seems unlikely given the relative import weights of these countries, according to the WTO (this is the report for the EU28, there is no report for the EZ):

Moreover, export demand may have fallen due to a slow down from emerging market demand, but low oil prices (assuming you are not an oil producing/extracting/refining fifm) should be a supply side boon, increasing output, even as inflation falls.

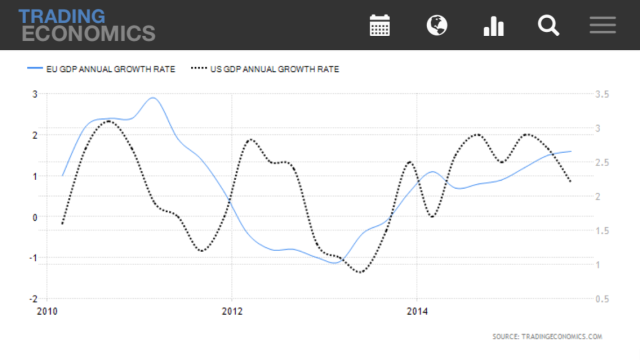

So what are the facts for the EZ? – what is actually going? Well, the economy is doing precisely what I just described.

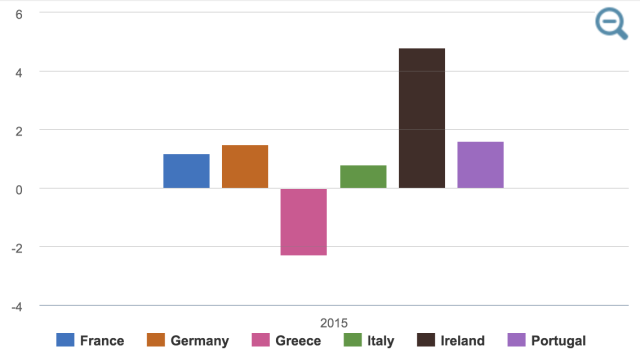

GDP grew at 1.6% in October 2015…

… and unemployment continued falling and reached 10.74%.

So low inflation is not that bad. It’s what you’d expect under these circumstances. The problem is two other things:

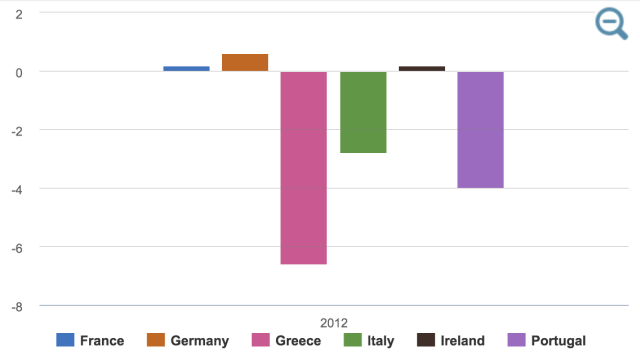

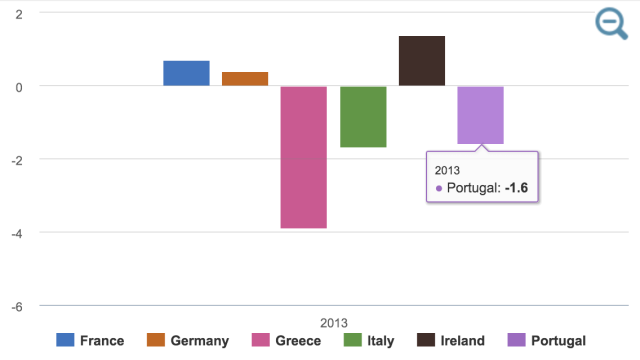

1 – On the one hand, we’d probably like to the EZ be growing faster, given how much growth collapsed in the previous years

2 – On the other hand, we’d probably like the growth to be either more equally distributed or more equally redistributed. As it stands variation has been pretty wide.

Evaluation

Inflation is really low, and I think that Draghi is exaggerating recent shifts. Inflation has not gone above 0.3% since October 2015 and spent 5 of the last 12 months in negative territory.

What we have has all the traits of supply-led growth. Despite forecasts and consumption signals I continue to doubt the ability of QE to facilitate a demand-led growth while government austerity holds back actual demand growth (C+I+G), even as I understand that the ECB is tied by its rules and the absence of a federal fiscal counterpart. This is not to say that QE has not helped. It’s been definitely supportive and the ECB should keep it coming.

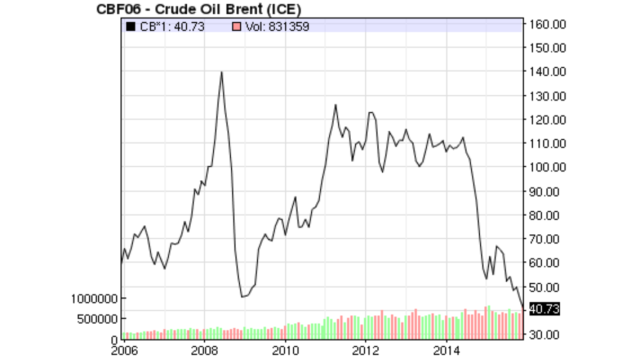

Of course inflation will go up eventually, but it will take time and will probably depend on oil price movements. However, what that means is that inflation may grow at the detriment of GDP, in which case the ECB may have to do more.

The way forward

My expectation is that inflation will remain subdued means the ECB is likely to continue to reinforce its policy. How so? By reinvesting not just principal repayments but also interest payments from the APP. Once oil prices rise, the potential slow-down in GDP may also force the ECB to extend QE.

There’s not much falling left for oil to do before it can only go up, or settle where it is for a while

(I would argue that it’s important to remember that OPEC upped oil output in order to price US fracking out of the market and that, short of a proper war in the Middle East (involving any two of Israel and Egypt, Iran or Saudi Arabia), this concern is not going anywhere, ISIS or not).

But of course I could be wrong…