Update: As of September 6th, 2012, the SMP was discontinued and the assets held in its accounts were transferred assimilated by the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) accounts. For a preliminary assessment of the OMT, please check this blog post. Otherwise, please continue reading below, for a review of the SMP.

—————————————————————————————–

Having looked at the tools available to the ECB, at its balance sheet, and at the transmission of monetary policy into the interbank lending market, after considering financial market failures due to Fractional Reserve Banking, overlending and VaR, I would like to turn my attention to the less orthodox interventions of the ECB. To this end I have already made some observations about the ECB’s Covered Bond Purchasing Programme. To these insights I now add a brief discussion of the Securities Market Programme.

Programmes of the ECB correspond to strategies it pursues, on a temporary basis, to deal with specific monetary problems, not always limited to, but often concerned with, liquidity shortages in the interbanking market and its negative impact on the transmission of monetary policy. The Securities Market Programme (SMP) is one such case. Below I look at the assets involved, what this programme pursues, the timeline of the intervention, its mechanics, its causes and its consequences.

While this programme of the ECB did not return sovereign debt markets to their path prior to the financial crisis, it would be unfair to state that it completely failed. Indeed there is evidence to consider that to some extent the SMP might have worked, when it was used.

What are sovereign debt bonds?

Sovereign debt bonds are financial contracts which are auctioned by the governments of sovereign states, as a means of financing their budget deficits. Through these contracts the governments of our countries acquire debt from financial markets. As with everything else they have a jargon of their own:

- Principal is the total amount being borrowed

- Coupon is “the interest paid on a bond. They are called coupons because formerly they were represented by physical coupons on the bond certificate that had to be clipped and returned to the issuer to receive the interest payment. With the advent of computers, this has become much less common.”

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is a specific rate of return “r”, say “IRR*”, at which the Net Present Value is equal to zero. It is not always possible to calculate IRR analytically.

- Net Present Value (NPV) = Sum[(Coupons)/(1+ r)]

- Yield refers to a specific formula used to determine the fair value of the bond. It normally refers to one of the following:

- Nominal Yield = (Coupon)/(Principal)

- Current Yield = (Coupon)/(Bonds Spot Market Price)

- Yield to Maturity = Total IRR

- Yield to Call = IRR until the bond is sold.

Government bonds are generally quoted in terms of their current yields. These quotes can be found in Bloomberg and interactive graphical data is available through it. Nominal yields are relevant at the time of a bond auction. More complete information can be accessed through Bloomberg terminals or through Datastream. If you are interested in following sovereign debt events, this blog provides regular weekly updates on upcoming sovereign debt auctions and reviews on the latest bond movements.

Mechanics of the SMP: How does it work?

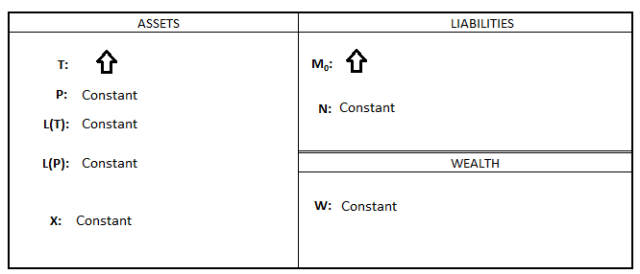

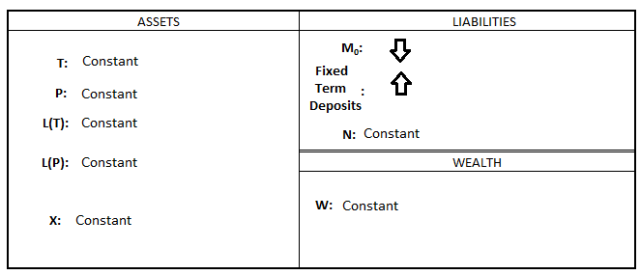

In that May 14, 2010, the ECB specified the details of the programme. The short version is that through the SMP, the ECB purchases government bonds, in secondary markets, in order to provide liquidity to alleviate pressures from sovereign debt risk on the balance sheet of MFIs. To limit the inflationary effects of those purchases, the ECB then sterilises these open market operations by auctioning fixed term deposits at the ECB, in order to stop the banking sector from increasing its loans to the overall public and increase inflation. Therefore, the SMP is effectively the official name of what would otherwise be known as sterilised debt monetisation. On the ECB’s balance sheet, this occurs as a combination of 2 steps:

Step 1: In a Structural Operations, the ECB outright purchases government bonds of some affected country.

Step 2: A Fine-tuning, liquidity absorbing operation, aimed at limiting the potential inflationary effects of the operation carried out in the first step.

Although the second step is done to alleviate inflationary pressures, the truth is that all that the sterilisation step produces is postponed inflation, probably at a premium proportional to term and risk free rate (clearly counter party risk do not affect the ECB

Fixed Term Deposits

Due to inflationary concerns, the ECB, ever-so-worried about price stability, attempts to sterilise the effect of its Securities and Market Programme (SMP), through which it purchases sovereign debt, by auctioning Fixed Term Deposits. According to the ECB, these are “monetary policy instrument[s] available to the Eurosystem for fine-tuning purposes. The Eurosystem offers remuneration on counterparties’ fixed-term deposits on accounts with the national central banks in order to absorb liquidity from the market”. This means that “when a term deposit is purchased, the lender (the customer) understands that the money can only be withdrawn after the term has ended or by giving a predetermined number of days’ notice”. By pursuing these operations, the ECB ensures that the extra liquidity of the SMP is held in reserves rather than going into operations and loans so that it does not multiply through the economy, thus slowing inflationary pressures. Of course this isn’t automatic. The process is still voluntary, so it can fall short of the target, in which case the sterilisation will not be sufficient and as such could possibly lead to higher inflation. Moreover, this is only a temporary solution, given that in these deposits will mature and the ECB will have to pay them back to depositors, with interest. Fixed Term Deposits are postponed inflation. Of course, under the present (2011-2012) circumstances, where economic stability is still a target rather than a reality, with (probably) spare capacity and scarce liquidity, this is not necessarily an issue, and thus one can be excused for thinking the ECB is erring on the side of caution.

Period of Operation

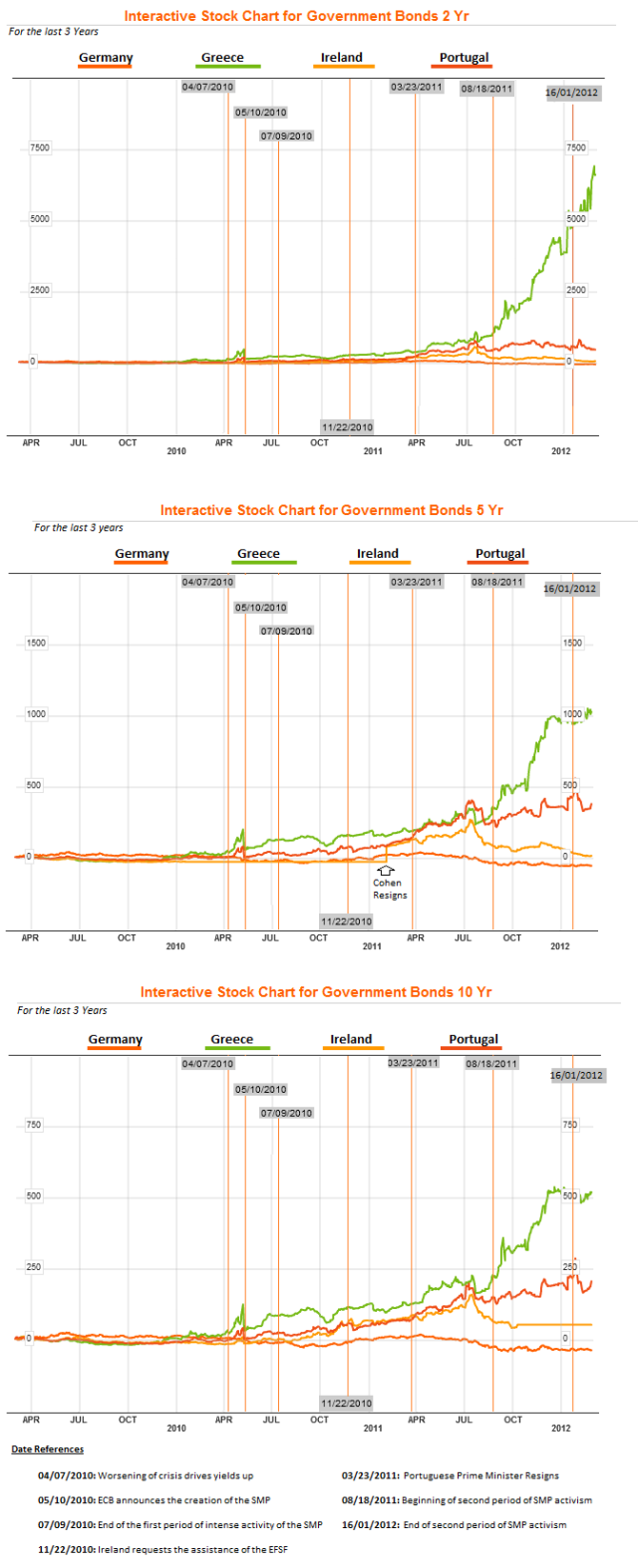

The Governing Council of the ECB decided to intervene in the secondary markets for “public and private debt securities markets” on May 10, 2010. The details of the intervention were later elaborated on in an ECB decision issued after the next ECB Governing Council meeting on May 14, 2010. The figure below illustrates the intervention of the ECB in government debt markets since the inception of the SMP until the last week of February 2012.

This figure shows that the SMP was mainly active during 2 periods. The first, immediately after its inception, lasted until the week of July 9 2010. The second period occurred between the week of August 15 2011 and the week starting on January 16 2012. This latter intervention was particularly active in its first weeks of operation, until October 2011, with fluctuations on its activity from there onwards.

Causes of the creation of the SMP

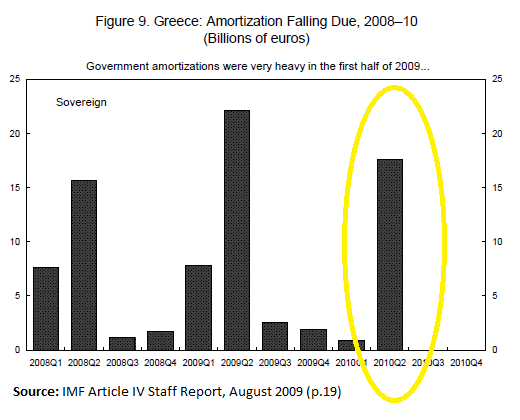

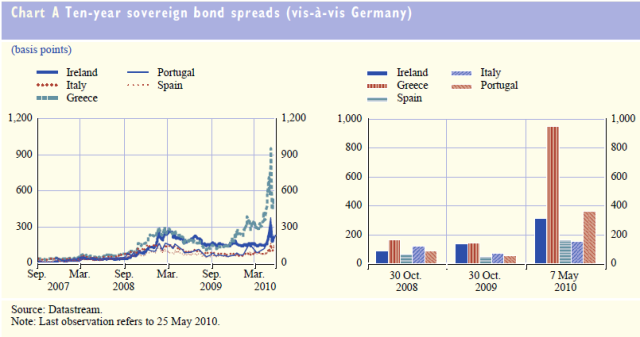

The creation of the SMP is closely related to the Greek debt crisis, which triggered the sovereign debt crisis in the rest of the continent. The rise of Greek bond yields started in September 2008 due to the liquidity shock created by the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. While it pushed yields upwards in all European capitals, this event had the added effect of decoupling Greek yields from the European neighbours it had been following for a decade. This decoupling accelerated from November 2009 as elections and a new government began to highlight discrepancies in the data collected domestically and the one provided to EU institutions. These fears gained momentum in December 2009 and January 2010 onwards, as the Council judged that Greece has not responded adequately to its March warning and the European Commission publishes a report recognising statistical fraud had occurred in Greece. Finally, the situation reached a critical point in April 2010, as the Greek state, unable to access credit in financial markets, seemed increasingly unable to find the resources necessary to pay an extensive amount of debt maturing in the second quarter of 2010 (The image below is taken from the IMF article IV staff report, published on August 2009).

This forced it invite a joint EC/IMF/ECB mission to Athens on April 21, 2010, with which it agreed an adjustment on May 2, 2010. However, it had become apparent that the problem was no longer confined to Greece. Indeed, as yields started to rise in Ireland and Portugal, contagion became the overwhelming fear. In an attempt to improve expectations and stabilise markets, European leaders agreed to the creation of the EFSF, on May 9, 2010. This fiscal commitment made intervention a justifiable policy path for the ECB which announced the creation of the SMP a day later.

This forced it invite a joint EC/IMF/ECB mission to Athens on April 21, 2010, with which it agreed an adjustment on May 2, 2010. However, it had become apparent that the problem was no longer confined to Greece. Indeed, as yields started to rise in Ireland and Portugal, contagion became the overwhelming fear. In an attempt to improve expectations and stabilise markets, European leaders agreed to the creation of the EFSF, on May 9, 2010. This fiscal commitment made intervention a justifiable policy path for the ECB which announced the creation of the SMP a day later.

In the May 10, 2010 press release, the ECB made the following statement

“The objective of this programme is to address the malfunctioning of securities markets and restore an appropriate monetary policy transmission mechanism.”

The ECB made specific mention to these and other issues in its Monthly Bulletins of May and June 2010.

Consequences of the SMP

I have been unable to find a full scale study of the effects of the SMP, similar to the one by Beine et al (2011) for the CBPP1. In my view, there are at least four major obstacles to doing this, none of which presents a researcher with a definite barrier to inquiry. First, the SMP is still in place and so, any measurement of its effects until it is over would be somewhat premature and incomplete. Secondly, the data is very opaque. On the one hand, data is only published weekly and on an aggregate value. There is no reference to when during the week they might have been bought. Moreover, the ECB does not provide a breakdown describing the composition of assets by national origin. Nonetheless, as Ugay 2007, Wieland 2009 and Krishnamurthy amd Vissing-Jorgensen 2011 make plain, Japan, USA and UK provide interesting templates for the study of the effects of this type of policy.

Not withstanding these facts, an independent analysis, although likely to be conducted on this website in the near future, is beyond the scope of this particular post. So for now, I will limit myself to the analysis of some time series, aided by the knowledge of the timing of some events.

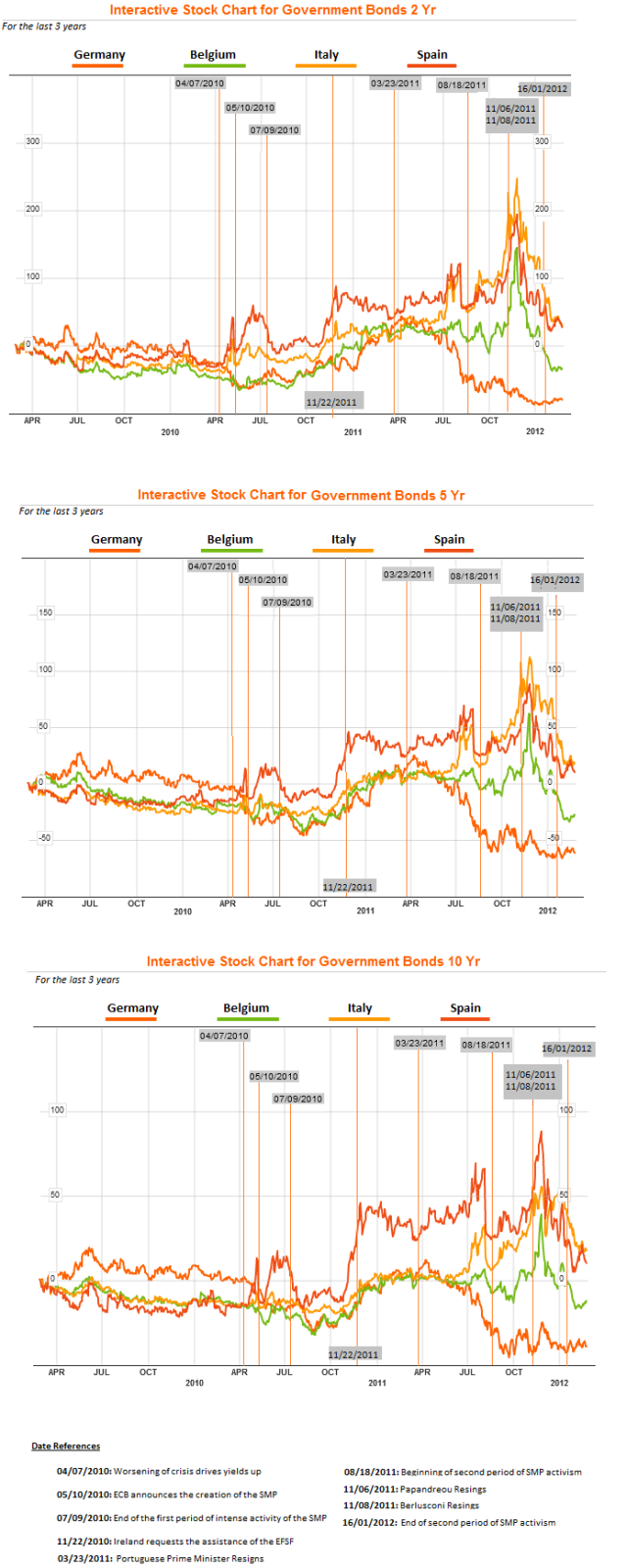

Assuming that the ECB’s goal in introducing the SMP was indeed to “restore an appropriate [and functioning] monetary policy transmission mechanism” to financial markets, by stabilising sovereign bonds, then it would appear that to date, the SMP has failed. Clearly as the figures below show, there is still turbulence in the markets. However, this very narrow interpretation of the consequences of the SMP would miss the details.

SMP: 1st Period of Activism

Considering the periods of intervention uncovered before, it seems that the first period of SMP activism by the ECB was relatively successful in bringing sovereign debt yields down. However its discontinuation led to a progressive rise in the yields of Greece, Ireland and Portugal. However, as the figure below shows, the second period of ECB activism did not have the same effect on the yields of the three bailed out countries.

SMP: 2nd Period of Activism

Interestingly, the effect of the SMP does not seem to be constrained to the countries above. Indeed, while the above might present a reactive behaviour on the part of the ECB, it is possible to describe its behaviour as of a much more preventive nature in Italy and Spain. As the figure below shows, and as was commented at the time, that the second period of SMP activism seems to have been targeted at managing Spain and Italy.

Between August and the beginning of November, the debates about PSI and the second Greek adjustment programme pushed contagion to Italy and its unresponsive political system. Moreover, the uncertain political climate in Spain, on the eve of the November 20 elections, inspired the volatility that is evidenced in the figures below. However, as bureaucratic governments took over in Italy and Greece as well as a more fiscally conservative government in Spain, the ECB’s intervention seems to have been more successful.

Although these descriptions might shed some light on the events that took place between 2010 and the Q1-2012, they are presented under no illusion of providing a causal explanation. It is impossible to tell whether the fall in Italian and Spanish yields was caused by political developments or by the ECB’s intervention without more sophisticated methods.

Although these descriptions might shed some light on the events that took place between 2010 and the Q1-2012, they are presented under no illusion of providing a causal explanation. It is impossible to tell whether the fall in Italian and Spanish yields was caused by political developments or by the ECB’s intervention without more sophisticated methods.

Conclusion

The SMP is a tool used for Debt Monetisation in the Euro-Zone. It is carried out in 2 steps and is meant to stabilise a specific financial sector responsible for monetary policy transmission: the sovereign debt markets. While this programme of the ECB did not return sovereign debt markets to their path prior to the financial crisis, it would be unfair to state that it completely failed. Indeed there is evidence to consider that to some extent the SMP might have worked, when it was used.

However, the fact that purchases were reined in to a considerable extent probably points to the fact that its impact on this specific financial segment was not as strong as the CBPP was or as similar programmes in the UK, USA and Japan. The conclusion must inevitably be that the ECB’s passivity and the fiscal austerity that accompanied it were the price of avoiding political moral hazard.

I was trying to send you a question trough you hotmail address, but apparently it does not work. So I will use the public comment. I was wondering whether the data you used for constructing SMP Purchases and Total are publicly available (I know that are available from the ECB website but in the press release) in excel spread sheet or similar.

Thank you very much for your help,

Caterina

Hi Caterina,

Thank you for taking the time to leave a comment. Following your comment about the email, I checked and it is working well, so I can’t explain the problem.

Regarding the data, you are right, it is only available on the ECB’s website as a press release. Given the announcement of the OMTs, I will soon post a figure with the full up-to-date performance of the SMP and the CBPP, as well as the relevant data set. Unfortunately, I cannot do that just yet because I haev not kept it up to date for some time.

I hope this helps!

I wanted to know where you are in the collection of data from the SMP. Is it possible to get the data you have so far?

Hi Sif,

Unfortunately I don’t know where I’ve put the data. I collected it for this post and then lost track of it. I’ll have a look and see what I can find, but I can’t promise anything unfortunately. Like I said, at the time, I compiled it from the Weekly Financial statements of the ECB. It was a bit time demanding, but if you just follow the dates and links on the post anyone can do it.

Hope it helps!

Best,

Filipe

Thx for this informative blog.

I do have a question about the Target2 issues. Probably you can give me an aswer to the following question:

Given all aspects of the euro crisis, the recent changes in the Target2 accounts, upcoming elections in the USA, coinciding with China’s 18th Party Congress in 2012, the 2013 elections in Germany and Italy and the proposals to reform the fundamental structures upon which the continuity of the euro system is to be guaranteed, the proposed SMP, is the ECB prepairing a transfer of its Target2 liabilities on her balance sheets to the ESM balance sheets?

And would such a move be possible?

Dear King Billy,

The answer to your question is that no, the ECB cannot transfer its liabilities to anyone, certainly not its target2 liabilites. It can sell the assets associated with these liabilities in the open market. However these liabilities are not as bad as people make them out to be. I’m in the process of writing a long post on this. Until I do, you may be interested in consulting the following websites:

http://www.ecb.int/paym/t2/

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2012/03/06/910081/getting-ones-head-around-target2/

Hope it helps. If not stay tuned for the post on this issue coming sometime soon.

Best!

Thx again. I stay tuned, and recommended your site to various Dutch readers and bloggers. However, correct me if I am wrong, but when EFSM became operational, earlier SMP’s for Greece were incorporated into EFSM as part of the haircut. Of course it’s an entire different issue than Target2 assets and liabilities, but a Dutch economist, Ad Broere, stated clearly that ‘certain junk’ assets in LTRO’s, SMP’s and dito colleteral for Target2 could be transferred to the ESM once a country applies for ESM funds.

After all, nothing is selled on the open market, but simply transferred from one balance sheet to another balance sheet.

As to the Target2 issues, I look forward to your comments! This discussion is not yet ended and given that the Treaty of Maastricht, -no bail-out, has been broken, and the the original purpose of the ESM treaty as well, and both the ECB and the ESM are not anymore free from political ‘massage’, my doubts.remain, as the ESM becomes for politicians more and more the instrument to socialise and institutionalise all sorts of debts, while adequate controlling mechanisms are brilliantly conspicuous by its absence.

http://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/kommentar-zum-esm-der-euro-fonds-11918361.html

http://www.volkskrant.nl/vk/nl/7264/Schuldencrisis/article/detail/3328036/2012/10/08/IMF-hint-op-afschrijven-noodlening-Griekenland.dhtml

Thank you for your comment. It made me realise I have never written about the EFSF, the EFSM, and the newly created ESM. I’ve been following this crisis for so long I forget that it is easy to get lost with all the acronyms. I started answering you with a run down of all of these, but then figured that given how long that part alone was, I might as well write a post dedicated to it. So thank you for the inspiration. 🙂

As regards Target 2 overdrafts, some of them do involve collateralised loans taken by peripheral commercial banks with their central banks, the collateral base of which might not be very reliable (certainly not MBS from Spain or the like). However, to my knowledge, there are no plans to transfer bad assets from national central banks, acquired under the SMP, to the EFSM, the EFSF or the ESM. While it is possible to do that in theory, in practice it would be quite difficult and in many cases quite undesirable because these funds have limited funds whereas the ECB has unlimited fire power, due to its very nature as the sole issuer of Euro. Any transaction such as the one you described would automatically involve a transfer of assets and liabilities. Given that, at the moment, the ESM and the EFSF have few and limited funds, acquiring such funds because they would be lowly rated would have to be considered as an intervention, not a capital investment and so would decrease their scope for intervention.

To my knowledge, there was only one idea about transferring funds from the ECB to one of the bailout funds and this did not involve Target2 balances. Instead, it was concerned with easing the pain on Greece. It was proposed that the ECB could take a haircut on its holdings of Greek debt in order to assist the hailing nation. The ECB refused, arguing that it would be tantamount to monetary financing. It was then argued that the ECB could sell the debt to the ESM at a discount (say by their market value). The argument was that the ECB would be profiting from the problems of Greece given that it purchased these assets at a huge discount and can expect, due to its institutional position, to see the full value of the principal and all the coupon payments come in. If Greek debt was devalued by 50% by the time the ECB bought it, it would (+/-) imply that for every €100m it can expect to receive back with interests, it only paid €50m. What that proposal stated was that the ECB should sell it to the ESM for €50m, which would make the ECB’s intervention neutral and provide extensive relief for Greece. The ECB continues to maintain that that would be tantamount to monetary financing. So no cigar. But who knows, it might still happen…

Hope it helps!

(Now let me try to finish that TARGET2 post…)

Again thx again, you wrote almost a blogpage as an answer. If permitted I’ll come back later to this issue because once the ESM becomes fully operational ‘politics’ will be involved. Tight rope cliff dancing while battling stormy weathers, so to speak -or write.

Bin mal gespannt, what your Target2 post will bring.

Just f.y.i., as a sideline, the following blogpost was recently over 2000 times visited since posted in Febr. ’12. Although in Dutch, it recently it attracted nevertheless worldwide attention after the ESM was formally installed during the European Council of Finance Secretary’s at Cyprus. Another sudden increase of visitors was seen when the ECB announced that colleteral offered by NCB’s would be more critically scrutinized..

Amongst others, from a row of uni’s and banks, worlwide. Apparently, there is more to the Target2 issue as it does not only function as a bookkeeping tool, underlining the unequalities of the economies within the eurozone.

Thanks! I’ll have a look!

I am working on my bachelor thesis in these days, and I have to admit this is the most useful website I’ve found so far, to collect datas, information and reference. I would really like to cite your research work about the SMP, the CBPP and the OMT, among the references. For now thank you in advance.

Best regards,

Luca Giustozzi

Hi Luca,

Thank you very much for your kind comments! I’m very touched. More importantly, I am glad to hear that you’ve found the content useful.

Best regards,

Filipe

Pingback: In defence of the (conflicted) ECB - Deflation Market